By Andrea Biondi, Research Fellow on the JPI Deep Cities project, University of Florence

Work Package 4 (WP4) is a section of Curbatheri project stricktly oriented to determine and to create an effective link between theory and practice. Its principal aim and deliverable is to create a toolbox to help the governance structures in the very difficult role of building, planning, and dismantling in stratified urban contexts. All the data elaborated through WP1, WP2 and WP3, made up by quantitative analysis and qualitative methods, will find a concrete synthesis in the elaboration of this digital-based toolbox

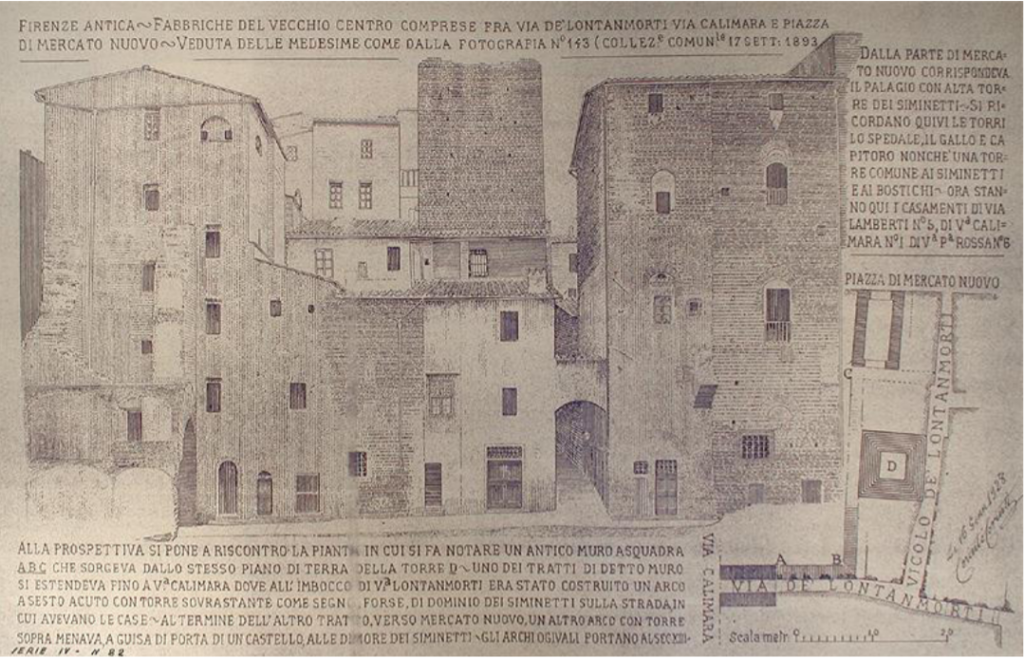

The city of Florence constitutes a very illustrative case of the destruction of heritage for urban re-planning (with still tangible consequences). In fact, between 1890 and 1895, the city experienced one of the most intensive (and destructive) urban redevelopment seasons in Italian history. The historic center of the city, corresponding to the current Piazza della Repubblica, in the very heart of the city, was literally destroyed with the cancellation of the Jewish ghetto and the medieval quarter near the ancient market square (the so called “Piazza del Mercato Vecchio”).

Tower houses, churches and the market itself were literally deleted in the name of progress, urban regeneration (against the ancient medieval city, seen as dark, dirty and smelly) and building speculation.

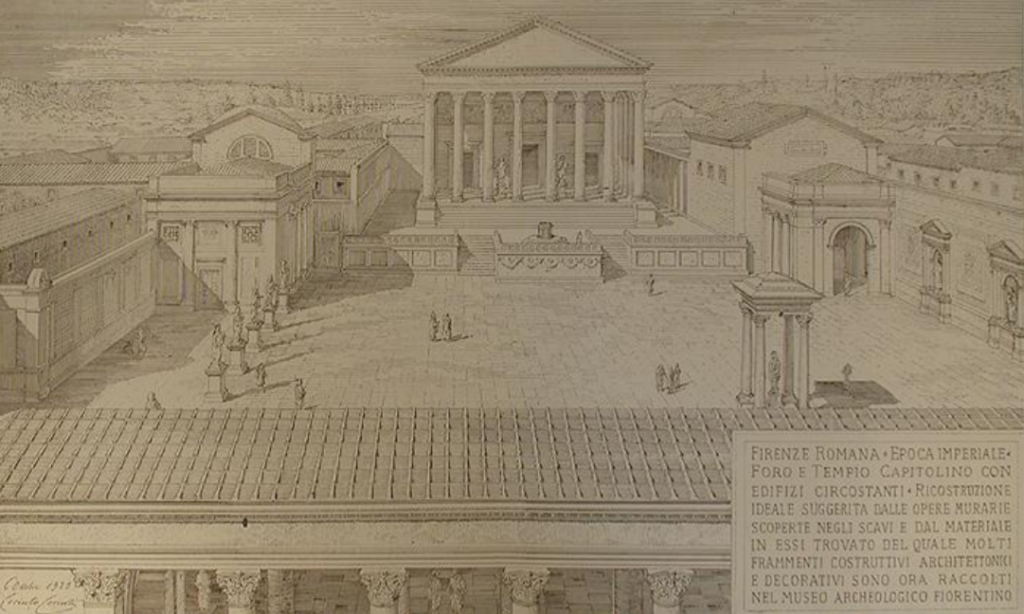

The same fate, starting from the 60s of the 19th century, knew the ancient medieval city-walls of Florence and several other monuments and buildings of its medieval past. The goal, of course, was that of a modern city. But at what price? Paradoxically, the operation described up to now provided also one of the few opportunities through which, thanks to the excavations, the vestiges of Roman Florence (ancient Florentia) were brought to light. After the destructions of the medieval and post-medieval archaeological levels and structures, in today’s Piazza della Repubblica the remains of Roman Forum and Capitolium were in fact discovered. Although afterwards, everything was covered up (or erased) and, above all, very little was published.

And what about public opinion? It was obviously divided: on the one hand most of the administrators supported the entire operation without reserve. The workers were equally oriented to a full involvement in the operation, by binding itself to an understandable material and employment needs. But the inhabitants? There were several voices of dissent and among these those of Florentine intellectuals, artists and inspectors of the local Superintendence.

The overall result, therefore, was a total remodeling of the area: a new and (largely) invented historic center was created, the population was forced to move to more peripheral areas of the city (including also some contexts in the vicinity of San Donato neighbourhood), and large parts of the medieval material remains of Florence past were destroyed.

Certainly, those were different times from nowadays: there were different needs, other goals, and a different approach to the past (above all to the medieval and post-medieval one). But are we so sure that it is a problem exclusively relegated to the 19th century? Ultimately, we think that a tool such as the Curbatheri online toolbox that will derive from WP4, in the hands of stakeholders, administrators, heritage professionals and active local citizens’ groups, will constitute a valuable key for the future more sustainable cities and for an urban planning more respectful of the needs and desires of the local communities and in line with the needs of democratization of decision making processes also for integrating (material and immaterial) cultural heritage into a wider urban development discourse.

Leave a Reply