By María Gabriela Navas Perrone, University of Barcelona and Margarita Díaz-Andreu, University of Barcelona/ICREA

L’Hospitalet de Llobregat is a town in the eastern part of Greater Barcelona. Walking through the streets of its urban area you can see traces of its past preserved in many buildings. This historical legacy forms part of an urban landscape in which lofty skyscrapers intermingle with public spaces enlivened by an effervescent social interaction.

Photo: María Gabriela Navas Perrone.

The tangible dimension of L’Hospitalet’s heritage is reflected in its urban morphology. This ranges from a Roman villa alongside the Via Augusta, the ancient road that linked the Roman towns of Barcino and Tarraco, to the medieval church of Santa Eulàlia de Provençana (built in the 12th century), the 13th-century Torre Blanca travellers’ hostel (hospitalet in Catalán), the early modern buildings, and the municipality’s most recent evolution as an industrial area. The Roman road still serves as the backbone of L’Hospitalet’s urban layout. In modern times its proximity to Barcelona led it to become a manufacturing area with substandard housing for workers and others who migrated to Barcelona in search of employment. This has meant that in the last two centuries L’Hospitalet has maintained a centre-periphery relationship with Barcelona.

Photo: Margarita Díaz-Andreu.

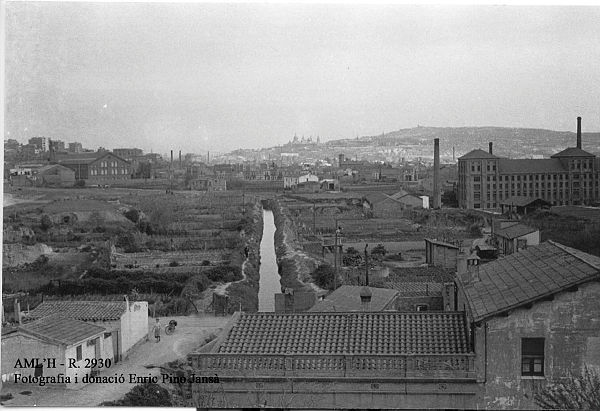

The 19th-century industrial boom was mainly driven by the provision of water from the Llobregat River via the Infanta Canal (1819), together with the implementation of the grid-like Cerdá Plan in Barcelona (1860) and the arrival of the railway (1854). These created many jobs in Barcelona and led to an urgent need for new housing. L’Hospitalet became a place of transit for many of these new workers, most of whom came from the Catalan countryside. They were initially received at the “Hospitalet”, a charity-run hostel for the poor. Attending to people passing through has always been a distinctive feature of L’Hospitalet and a key element in its urban development. It has been marked by speculation in the housing market and the reception of migratory waves as a historical constant. Its uncontrolled urban growth has given the town one of the highest population densities in Europe and has led to significant urban and service deficits.

Source: L’Hospitalet Municipal Archive.

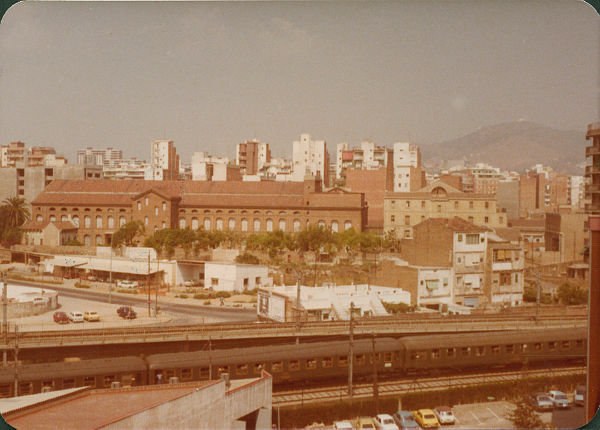

The town’s industrial heyday in the 1870s can now be seen in some of the buildings that used to be factories and have now been converted to other uses. This can be illustrated by the Tecla Sala complex, one of the most important textile factories in Spain from 1886, whose closure in 1973 was due to the general crisis in the textile sector. In 1982 the premises were bought by L’Hospitalet Council and converted into a cultural centre. Together with this factory there are others protected by PEPPA, the Special Plan for the Protection of Architectural Heritage of L’Hospitalet (1988): the Godó i Trias factory, Can Llopis, Can Batllori, Can Vilumara, Albert Germans, Can Gras and the Antiga fàbrica d’olis [former oil factory].

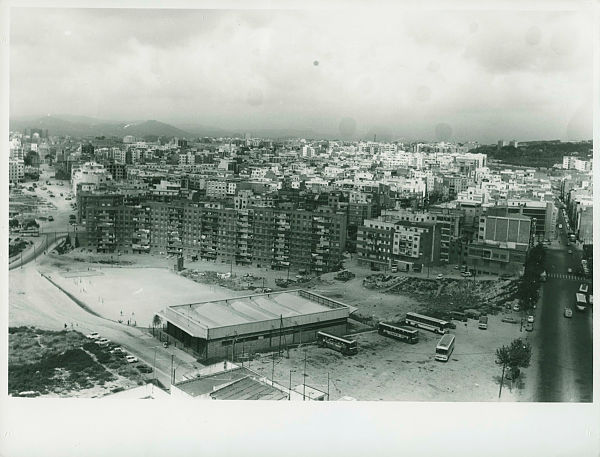

In the 1960s, the urban space dedicated to industry covered approximately a quarter of the municipal area. However, the economic crisis of the following decade and the beginning of deindustrialisation led to the closure of several factories and the inevitable loss of jobs. The number of inhabitants, nevertheless, increased at this time, as those who perhaps would have left had nowhere to go. At this time Spain was going through a process of mass migration from the rural areas to the largest cities. In L’Hospitalet this led to land speculation and the construction of new housing estates characterised by cheap materials and the lack of necessary infrastructure where newcomers from all over Spain found a place to dwell.

The dismantling of L’Hospitalet’s industrial area coincided with the country’s transition to democracy in the late 1970s and early 1980s. At this time property speculation was counterbalanced by a series of reforms, such as the construction of roads, the improvement of transport services and the upgrading of the sewage system, together with additional educational and cultural facilities. All these were put in place in response to the demands of the neighbourhood movements. In the 1960s and 70s, new neighbourhoods grew up in L’Hospitalet: La Florida, Pubilla Casas, Sant Feliu, Bellvitge, Can Serra and El Gornal.

In the 1990s, strategic planning led to grandiose urban projects, such as the Plaça de Europa, the City of Justice and the Fira de Barcelona. Despite the fact that all these were somehow connected to the image of Barcelona, they also helped to regenerate the image of L’Hospitalet. The construction of these emblematic architectural projects strategically assisted the regeneration of this image. The idea was that L’Hospitalet was a marketable brand capable of competing within the metropolitan area of Barcelona and in this way it attracted investment from the financial sector and the international tourist sector. This conversion of L’Hospitalet into an image offered to the market to produce capital gains is the context that is still today the basis for the preservation of its architectural heritage.

Source: El País / news feature entitled: Why is L’Hospitalet de Llobregat the Spanish city where the price of housing has grown the most in five years? / Photo: Ferràn Nadeu.

Today we can still note the tension between property development and the preservation of architectural heritage in the area where the Cosme Toda factory once stood. Its inclusion in the 1988 Special Plan for the Protection of Architectural Heritage (PEPPA) did not stop the current construction of a complex of 24 blocks with 885 flats. This new development will further increase the population density that L’Hospitalet has suffered from for decades. In fact, it will make the problem worse by attracting people who cannot afford the exorbitant prices of flats in Barcelona, which are completely out of the reach of the working classes. The consequence of this is demographic mobility, as the town is attracting a type of population with greater purchasing power, while excluding the local population. This means that a new era could be dawning in at least some areas of L’Hospitalet, where many years of welcoming newcomers to the Barcelona area may be coming to an end. The town may be on the verge of a gentrification process, attracting those with certain means and jobs in Barcelona. This means that L’Hospitalet is experiencing urban and property pressures that may jeopardize not only the preservation of its architectural heritage, but also the conservation of the social fabric of its neighborhoods.

Photo: Margarita Díaz-Andreu

What is the role of heritage in the dynamics of urban commodification? The image of L’Hospitalet as a hospitable city that is ensuring that at least some of its industrial past is being preserved may, in fact, be obscuring the effects of social expulsion. The social base of the town has changed in the last two to three decades, with many of the newcomers now having been born in other countries. L’Hospitalet, therefore, continues to be the first port of call for those attracted to Barcelona but who cannot afford to live in the big city. However, keeping heritage alive may be promoting a conversion of the city into a factory for the production of urban capital gains. Can this process be reversed? The Deep Cities approach is a contribution to identifying the tangible and intangible values of industrial architecture that deserve to be preserved in order to promote sustainable urban solutions capable of reversing the socio-spatial effects generated by the commodification of heritage.

Leave a Reply