By Torgrim Sneve Guttormsen, The Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU).

Archaeologists, like myself, are familiar with finding fragments from the past in present cities. However, the city’s archaeology is more than excavations and discovering things and structures hidden in deep urban historical layers.

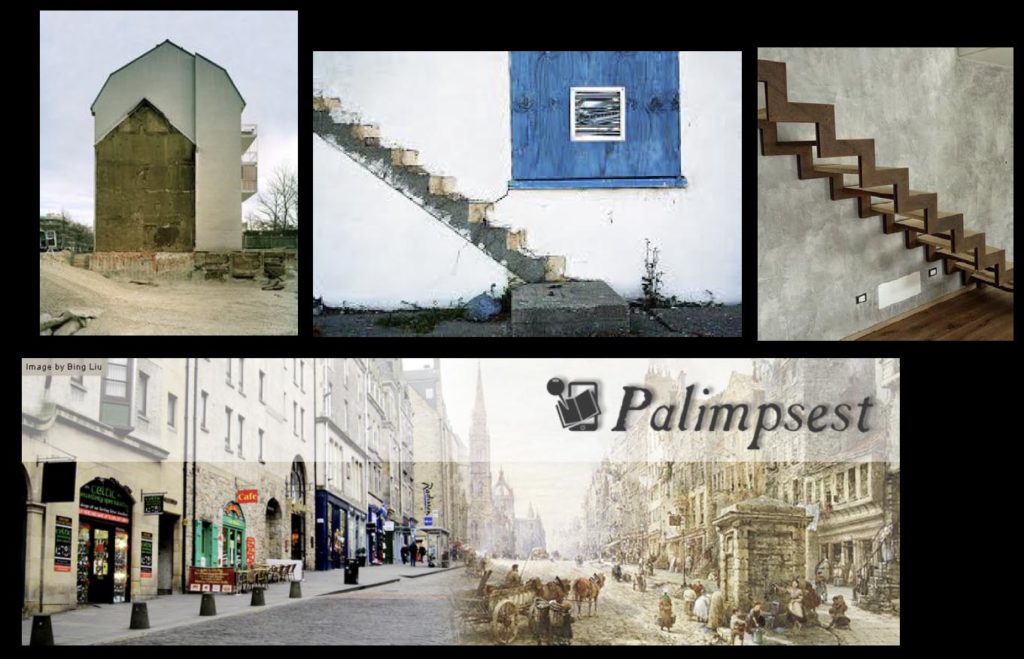

Archaeology as a reflective practice promotes a way of thinking about the fragmented cultural heritage of the city. Archaeological traces, ruins, and fragments are material manifestations of the continuously historical transformation that makes “new cities” on top of its “old” foundations. The “layered cities” extract the temporal dynamics of cities from the past which will continue forming and transforming into future “layered cities” represented perhaps by underground malls and skyscrapers stretching into the skies.

A question for investigation is how these ongoing urban changes, and the heritage that is produced, would become waste that will be thrown away or heritage to be valued and used in sustainable urban planning.

The question becomes relevant when recognizing the difficulties of preserving the the ‘frozen image’ of a specific historical time. Represented by intact historical environments such as whole building complexes, quarters and parks, which in no small extent, their integral aesthetics have been prioritized in post-modern practices of conservation and planning.

Some heritage experts believe that the fragments and traces of past structures, in comparison with entire building or parks, have minimal value. These are often seen as historic information capsules which function is the anecdotal source material for showcasing the history of a place. It is obvious that the preservation of entire intact historic cities or urban spaces, as in Venice or Montepulciano in Italy, provides significantly more historical information than the conservation of fragments of these cities.

But the fragmented heritage also embeds heritage values and become resources for creating new urban spaces. The examples are many: Ruins used in new urban design for restaurants, bullet holes in Berlin from the WW2 as for instance shown by “The Bridge of Scars”, or valuing buildings and spaces of decay and petrification such as shown by the archaeologist Julia Solis in “Stages of Decay”. Fragmented cultural heritage has become a valuable resources found in ideas of circular economy (vintage design, used furniture, etc.) and in heritage products that use patina or the absence of heritage as a source to create something new.

Another primary concern has been that heritage management that helps to legitimize anecdotal protection by valuing fragmented heritage will weaken the role of the heritage management for a sustainable urban development, and open up for developers who want to destroy cultural heritage in cities for given space to new building structures or infrastructures.

The concern is justified, but what do we do with the fragmented heritage that is already there? Dynamic cities cannot be ‘frozen’ by a conservation strategy where cultural heritage is perceived as static and immutable, as a closed container or glass showcase, also called a ‘bell jar’-protection strategy. That is why most cities preserve their past based on their fragments, because they are ever-changing.

In my opinion, we must therefore be able to allow for both perspectives: both heterogeneity and homogeneity, as a conservation strategy. The cities that will flourish in the future are the dynamic cities that cope with change and have the capacity to adapt to new needs and at the same time bring with them the city’s long-term memory as a vital resource. In urban development, concepts such as ‘smart cities’ (the technology city, the digital and interactive city) and ‘green cities’ (the environmentally friendly city) are used.

But it would be both wise and profitable to also draw on the concept of ‘deep cities’, which is about the city’s temporal history and the value of change as a prosperous heritage perspective. ‘Deep cities’ can help create robust cities by combining new and innovative solutions with the preservation and strengthening of the historic functions.

Leave a Reply