By Ted Grevstad-Nordbrock

Grevstad-Nordbrock is an Associate Professor of Preservation and Cultural Heritage in the Department of Community and Regional Planning, College of Design, Iowa State University. He is a Fulbright Scholar (Norway) for the Fall semester of 2022 and based at NIKU’s Oslo headquarters.

As I understand it, Deep Cities provides a theoretical approach to heritage that emphasizes the juxtaposition of past and present and the plays off the fertile schisms that can emerge where they intersect. This might include physical fragments from one era that exist incongruously alongside those from another: a medieval wall incorporated into a contemporary restaurant; the arced outline of a former tram route recorded for posterity in the surface of a modern public park. Jarring juxtapositions can accentuate the old but also draw attention the new. They highlight the inexorable passage of time and the fleeting nature of culture, as well as its tangible remains. “Time goes, you say? Ah no! Alas, Time stays, we go.”

Although I’m writing from Oslo, Norway, I live and teach in Ames, Iowa, a small Midwestern town with a large public university located north of the state’s most populous city and capital, Des Moines. Two historic houses here, and a site related to a former residence, provide me with an opportunity to reflect on the concept of Deep Cities and how we reckon with a growing catalog of fragments from the past.

The Knapp-Wilson House, known locally as the “Farm House Museum” (Fig.1), is the oldest building on the Iowa State University campus. Its earliest sections date to 1861. The rather non-descript house—significant for its history, not its design—was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places four years later. Beginning in 1970 and concluding in 1976, the American Bicentennial year, the house was restored to its early-20th century appearance, its “period of significance,” with missing materials recreated and more recent additions removed. As it stands today, the Farm House represents a conservative and traditional solution to the problem of preservation.

Physical change to the building has been arrested. Architects and curators from the university’s museum have chronicled the house’s history by focusing on a single moment in time. Its history has been reduced and repackaged for students, both current and prospective, as well as visiting alumni. As the oldest extant building on campus, and tangible proof of the institution’s ‘ancient’ roots in 1858, a philosophy of ‘preservation in amber’ was the preferred mode of intervention for preserving it. As the university has grown from a sleepy agricultural college to a bustling research university, the stolid Farm House now seems to stand unperturbed by the seachange that has enveloped it. As the National Register nomination notes, the poignancy of the Farm House is enhanced by its surroundings, since it now sit incongruously “in the midst of a large campus”.

Not far from the Farm House, on the opposite side of Lincoln Highway immediately south of campus, the Washington J. Graham House used to stand. Today it has largely been forgotten by Ames residents and students. Yet hints at the house’s erstwhile existence are still discernable on the cityscape. Roughly contemporaneous to the Farm House, this small, two-room cabin was built by an early pioneer to central Iowa, an settler who likely had a hand in the establishment of the university. Little is known about Graham and his life in Ames. It is assumed that his brickyard supplied the materials that went into the earliest buildings on campus, some of which remain. He is also thought to have sold land to the state for the establishment of the university. At best we can surmise that Graham’s history is a mix of truth and apocryphal speculation.

For a century the whereabouts of Graham’s house was unknown, had anyone thought to inquire about it. In 1951 it was rediscovered, serendipitously, during the demolition of a seemingly insignificant frame house near campus. What historians later determined to be Graham’s pioneer home was found encased within the newer structure—a relatively common occurrence in towns along the shifting western frontier, where building materials were scarce and oftentimes salvaged and reused or integrated into subsequent construction. Nascent preservationists saved the house by moving it several blocks east, out of harm’s way, and restored it to the standards of the time. There it stood for the next twenty years as a rental property. On July 4, 1976—Independence Day—the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution unveiled a plaque at the original site, by then redeveloped as a fast food restaurant (Figure 2). The stone-mounted plaque commemorates Graham’s cabin as ‘first house built in west Ames’ and references the 1951 move that ensured its preservation.

Yet the story doesn’t end there. With little opposition the privately-owned Graham House was demolished in 1996, twenty years after the plaque was unveiled, to make way for off-campus student housing (Fig. 3). Lamenting its loss in the local paper, a reporter noted how the house’s “destruction… was helped by the fact that city officials had lost track of its move…”, this despite the presence of the plaque which established a thread between its original and new location.

Today, the Graham House site-cum-Dunkin’ Donuts is marked by a plaque directing its reader to a second site on which “the first house” of west Ames formerly stood. We might rightly interpret this as evidence of the expendability of historic places in American cities and the lack of a cohesive effort to identify and protect vestiges of our past. But I would also argue that this marker, with its outdated reference and allusion to a void in the historic landscape, reveals more now than perhaps it once did, when its point of reference was still accurate. In pondering such changes to the ever-evolving urban landscape, Fouseki, Guttormsen, and Swensen pose the question, at what point does new development represent ‘an added layer of value to the palimpsest of the [deep] city or a threat to [its] continuity’? Here, the artifact has been expunged from the landscape and all physical traces long removed. Yet the allusions remain and, in some sense, add to the palimpsest and tell a compelling story about change in this college town. A palpable absence here is a more evocative quality than a continued presence might have been.

To me, the Archie and Nancy Martin House (Fig. 4) is an illustrative example of how the Deep Cities framework can help reimagine and interpret the past. This mundane bungalow dates from the late-1910s, when many such houses were being erected across the American Midwest. It stands on Lincoln Highway just over three kilometers east of where the Graham House originally stood. In almost every sense the Martin House is unremarkable. Its historic significance lies not in its physical fabric but, like the Farm House on campus, with its historical associations—in this case with its original owners and long-time residents, Archie and Nancy Martin. The story of this husband-and-wife couple (Fig. 5) is a fascinating one. Both were born into slavery in the American South, and like many African Americans in the wake of the Civil War, they moved north to find opportunity in the comparatively tolerant environment of Iowa. Through a friend in Georgia, they found their way to what was then a growing college town on the plains, a short train ride from Des Moines. The Martins are celebrated today for providing housing to Black students during a time when they could attend the university but were prohibited from living on campus with white students. Their house effectively removed an obstacle to enrollment and also became an impromptu hub for the small African American community of Ames.

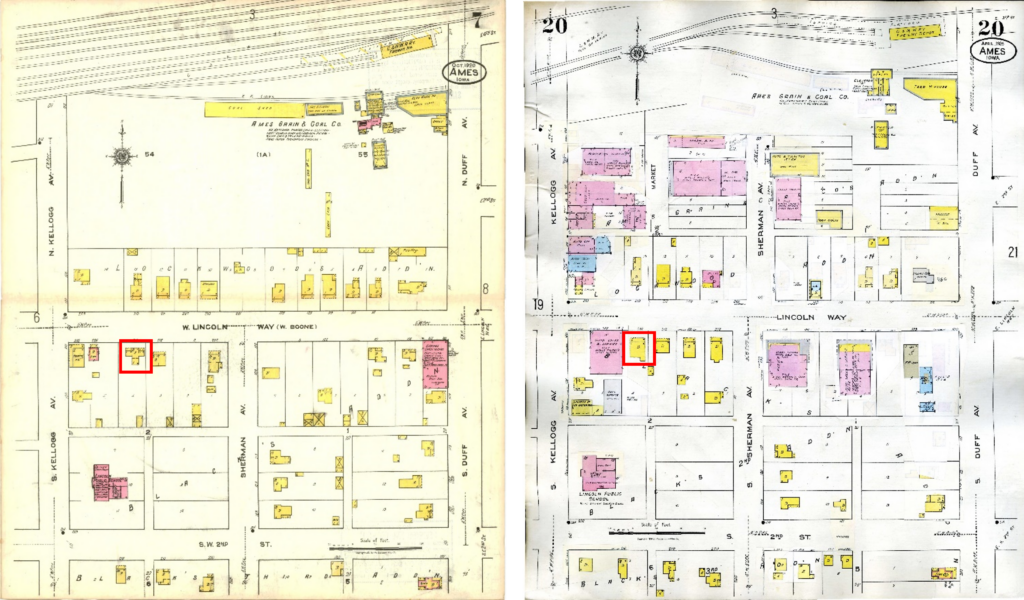

The location of the Martin House is significant. When the Martins designed and built their home it must have seemed a marked improvement from what was available to them in the South. Yet discriminatory real estate practices likely limited where they could build in Ames. A stretch of the newly established Lincoln Highway, one of the first transcontinental roads in the US, connecting New York City to San Francisco, was one such place. Highways accelerated the change in land use along their courses. Stable residential neighborhoods in cities and towns became commercial or industrial, and this is precisely what occurred in Ames (Fig. 6). It is no coincidence, then, that an African American couple in a predominantly white town found a building site along what must have seemed a transitional and increasingly marginal neighborhood.

Land use along Lincoln Way continued to change over the course of the 20th Century. Today, the Martin House stands in isolation (Fig. 7) in a way that poignantly speaks to the reality of race as a determinant of residential location, even in northern states. The Martin House serves as a reminder that places, no less than individual buildings, are constantly in flux. Not only can this not be arrested, but this mutability can also help shed light on the past in ways that static preserved buildings and environments often cannot. As the Deep Cities project notes, ‘A characteristic feature of cities is… that they are constantly changing, and have historically been in transformation’. If its post-rational aesthetic predilections allow for the acceptance of ‘ruins, rubbish, junk and trash’ as history and heritage, then the change in land use that has isolated the Martin House is very much a part of this expanded conceptualization of heritage.

College towns are unique as places of teaching and learning. Most pedagogical activity occurs in the rarefied spaces dedicated to education, both on campus and online, and altogether too infrequently in the world outside the classroom. The three sites presented here were chosen with the concept of Deep Cities in mind. When taken together, they offer competing visions of the role that heritage can play within a community. The preserved-in-amber Farm House presents a traditional, sanctioned version of heritage interpretation, an authorized statement by its owners, a university, that serves to communicate and reinforce its own origin-stories. The Graham House site/Dunkin’ Donuts, with its discordant marker celebrating a historic preservation victory and a landmark subsequently razed, unintentionally reveals an earlier generation’s simultaneous affection for, and ambivalence to, built heritage. The Martin House is perhaps the most complex site of the three. On the one hand, it has become a touchstone for the city’s and the university’s celebration of its modest African American history, a companion to the many memorials to alumnus George Washington Carver (of peanut fame) and doomed college football player Jack Trice. Yet the Martins’ old house at its isolated location along a traffic-clogged section of a transcontinental highway speaks volumes to the reality of race relations in the US.